Behavior Charts Encourage Fear and Inequality in the Classroom, and It’s Time to Get Rid of Them

Relationships are everything when it comes to teaching.

I work at a year-round school in Portland, Oregon, in a community rich with family and cultural tradition. It’s a neighborhood where kids still play outside until dark and neighbors are more like aunties, babysitters, and friends. Our classrooms are a refuge for students looking for a friendly face, a deep sense of belonging, or just an afternoon snack.

Yet, none of this would be possible without the relationships between teachers, parents, and students. I think our success is due to our focus on engagement and community over discipline and compliance. And for me, part of this means you won’t find behavior charts in my classroom.

The talk of discipline dominates the conversations in education.

I’ve been in teaching long enough where I understand the challenges and struggles teachers face every day. On many campuses and in schools, the sole focus of success centers on student behavior. In fact, so many people in education zero in on it that it becomes the single action item in our Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), Student Intervention Teams (SIT), Climate Plans, and Individualized Educational Programs (IEPs).

Teachers are tired of talking about discipline. We are tired of redirecting, writing referrals, changing seating arrangements, withholding student recess, calling home, and reading books on what we need to do for good classroom management.

Large class sizes, lack of district support, and just overall fatigue make it hard to deal with the daily struggles of student behavior. It makes it hard not to take it personally when our kiddos show up and disrupt classroom learning in ways that are extremely challenging to handle.

But you know what doesn’t work? You know what doesn’t magically have kids listening and paying attention? Behavior charts. They don’t work.

Behavior charts should work in theory.

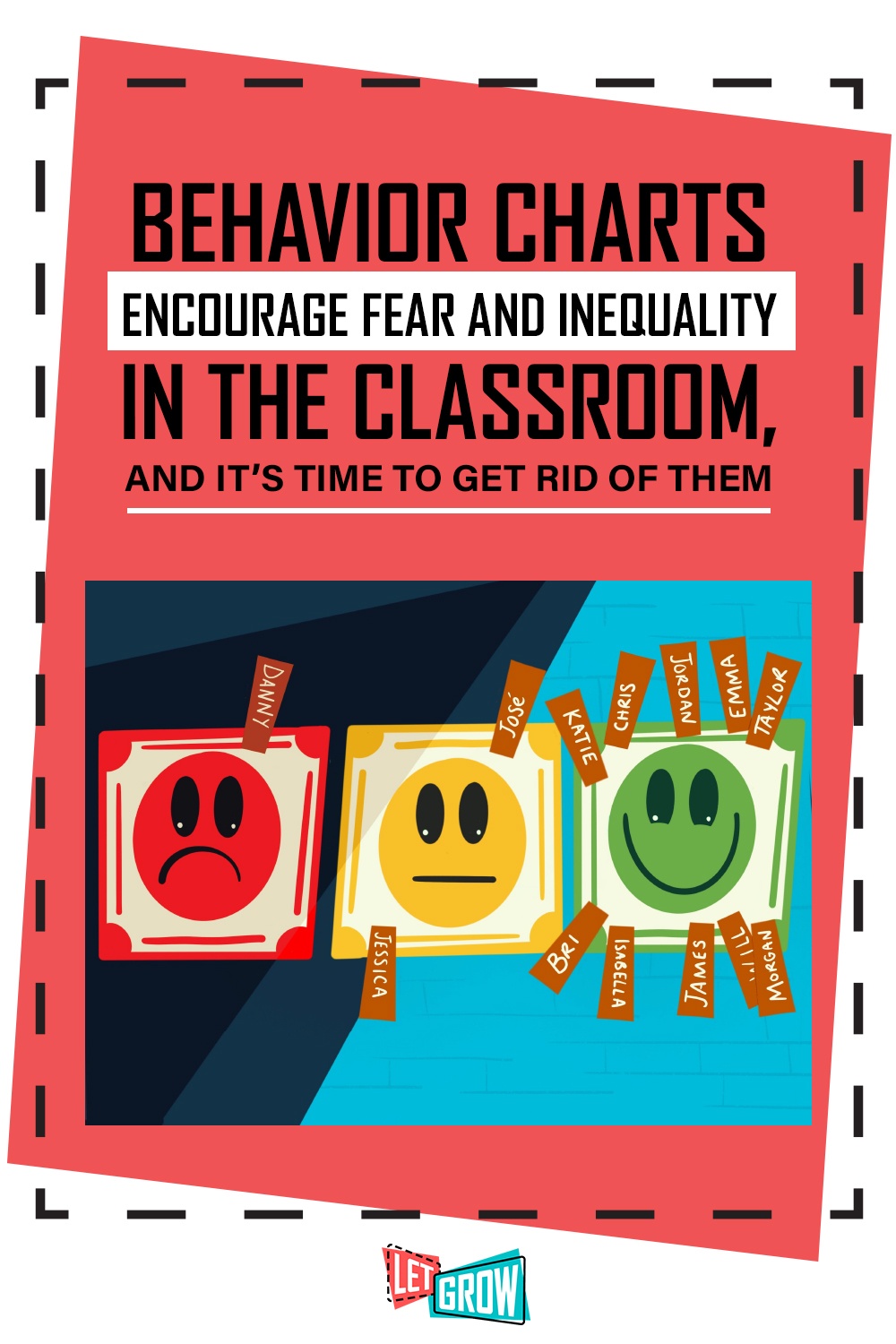

In our search for strategies that help us better manage our classrooms, many of us have turned to behavior charts at one time or another. These charts are large displays in the classroom that indicate how students compare to each other in areas such as homework completion, respect for authority, timeliness, workspace cleanliness, and compliance.

To be completely honest, I can see how behavior charts might seem like a really good idea. They might even be used for positive reinforcement. For instance, good behavior doesn’t always get much airtime in the classroom. We spend so much time calling out and redirecting. It’s easy to overlook the students who are always on task and come prepared for learning. This is where a behavior chart could be great to recognize those positive moments.

So, what’s the problem? Well, at face value, nothing. Behavior charts, like any other tool, can be useful in monitoring behavior and celebrating the students who meet our classroom expectations. But we all know there’s more to behavior charts than rewards, setting expectations, and data.

Along with positive reinforcement for some, there’s negative consequences for others. With the charts that have a rating system (numbers or colors), kids can get promoted or demoted by doing one single act. This is great for positive acts, but it’s not so great for the others.

Imagine you’re a 5-year-old. Mornings just aren’t your thing in general, but you’re also tired and a bit hungry because you woke up late and didn’t have time for breakfast. You get to school and settle into your classroom. Then during morning announcements, you don’t make the best choice. “Go flip your card!” the teacher says.

It’s 8:45 AM, and you just got on red for the rest of the day. Everyone watches while you go move your card to red. You know you’ll have to take a note home at the end of the day. And there’s nothing you can do to get back on green. So much for having a good day.

Classroom management is easy to talk about but much harder to put into practice.

To better understand behavior charts, it helps to know the background. Behavior charts stem from the father of operant conditioning, B.F. Skinner. When we investigate terms like positive reinforcements or classroom reward systems, we discover the theory that behavior is learned based on consequences and rewards. And we see this Token Economy prevalent all around us in classroom behavior charts, school-adopted programs, like PBIS (positive behavior interventions and supports), and within online platforms, like Class Dojo.

However, these systems and theories don’t always work well in practice. Teachers can have all sorts of expectations about having students with positive behavior who comply in the classroom. But then you get into that classroom, and it’s a different story. And much of our practice focuses on what’s wrong with the student rather than what happened to them.

You come across kids with significant trauma, high emotional needs, and social behavior that behavior charts just can’t touch. In addition, you find that some kids just don’t respond well to positive reinforcement or tracking their daily behavior with a clip or color system—it just doesn’t work.

And let’s get real about how they might negatively impact kids. Now, if we can hold the perspective that behavior charts make sense for some, we should also be able to hold the perspective that they can cause considerable harm to others. They also perpetuate the racial disparities we know are inherent within our classrooms.

We’re not teaching the whole child; we’re teaching kids to be quiet and compliant.

We know what the data says about discipline, especially when it comes to our historically underserved students. We’ve read about the need to recruit and retain more educators of color. And we’re aware of how, in spite of landmark law cases, like Brown vs. Board of Education Topeka, segregation is still very much alive and well throughout public education. It’s these truths that make it important, as educators, to investigate the potential harms in how we implement behavior charts, and any other form of classroom management in our classrooms.

When I think about my Black and brown students, I am mindful that much of what we expect in the classroom stems from values consistent in the dominant culture. Pipelines like school to prison and school to deportation are the first to come to my mind when I consider the expectations on most behavior charts I’ve seen throughout classrooms.

I’m an educator who is not satisfied with districts whose response to classroom management is to embarrass our children into compliance. Maybe you are too. A more critical analysis of behavior charts (or any system for that matter) would be questioning what it is we truly believe about education and our students in order for us to result to such a primitive expectation of conditioning our children.

Let’s change it up.

I believe we can do better. We need to give kids a learning environment where they can see themselves and have a say in their own learning. One where they can show up unapologetically and without judgment. A classroom where they are celebrated.

From my perspective, behavior charts don’t do these things. Instead, they encourage kids to act out of fear or shame. They also have kids constantly comparing themselves to their peers instead of focusing on their individual needs or strengths.

So let’s stop using them. If your school or district requires them, pull together the research to make a case against them. Better yet, talk to like-minded colleagues and approach it as a team. Or if you’ve just been using them out of habit, just stop. It’s your classroom, and you have your students’ best interest in mind. You probably know of better ways or approaches to try, so go for it. Your students will definitely benefit.

Comments are closed for this article.