Let’s Stop Telling Our Kids to Be Careful All the Time

I see my son suspended in the air above me, and for a split second, my breath catches. This confident kid is climbing a tall pine limberly, leaping from one solid branch to the next with more grace than I’ve ever seen him eat dinner or put on his shoes. His feet don’t seem to even touch the boughs as he dances from one to the next. It’s mesmerizing to watch, and there’s a moment when I forget just how high he is.

But then one foot slips just a quarter of an inch, and he loses his momentum. He pauses, perched on an outstretched branch like a squirrel poised to launch. I can see him mentally calculating the distance to the next step, and when his feet push off and his arms outstretch, I see him frozen there for a second, like time has paused.

“Be careful!” I shout, the words falling from my mouth before I even knew they were there.

For a fraction of a second, his eyes dart away from the tree and land on mine, wild and confused. His foot misses the next branch and instead of grabbing the one above it, his arms drape over his intended landing spot while his stomach cushions his fall and his feet kick out until they finally find a new hold.

“Mom!” he yells, and for a second I can’t tell if he’s hurt or angry, or both. “You messed me up! Why did you do that—I was fine!” He is scurrying down now, the game over and the magic is gone. He throws his backpack over his shoulder and takes off towards home. I trail behind.

What was the point of that?

I hadn’t meant to break his concentration from free play, and I’d only spoken up out of concern for his safety. Before he leapt, I just wanted him to think another second. Rather than launching his whole body at once, I wanted him to purposefully extend one leg at a time. I wanted him to notice the rotten branch, without any pine needles, right next to the one he was aiming for.

That’s what I really meant when I yelled to be careful, but I know that’s not what he heard.

I’ve said this phrase a thousand times in his short seven years, and at this point, it’s just background noise to him. Except sometimes it’s not and it comes out noisy and clipped, like this time when I broke his concentration. I meant to help, but really I just made things worse.

So, what is it about those words—Be careful— that makes them often so ineffective? In my son’s first grade classroom there is a sign on the wall that says:

THINK before you SPEAK.

T: Is it TRUE?

H: Is it HELPFUL?

I: Is it INSPIRING?

N: Is it NECESSARY?

K: Is it KIND?

Although this is obviously designed for interactions between classmates, I believe we parents can learn from it, too. Before we yell “Be careful!” maybe we should ask ourselves some of these same questions. Is it helpful, is it inspiring, is it necessary to our confident kids?

What does the phrase even mean?

Let’s start by looking at the necessity. We already know children hear this phrase of caution too much. Adults use it in loosely in nearly every facet of their lives. Teachers murmur it over their shoulders as they begin to fill in an answer on their math sheet. Coaches yell it from the sidelines when an opponent is coming up quickly from behind. One parent says it to the other as they pull out into traffic or push the baby on a swing.

The words are simple enough, but they’ve been used with such frequency that they no longer hold any power. They’re no longer necessary because they’re rarely even heard. The words themselves have become redundant.

Next, let’s ask ourselves if these words are inspiring. They’re definitely not. If anything, they’re just fear-inducing, spoken from our own worries and concerns. Teachers, coaches, parents, friends, mentors—we all want to see our children succeed. When we tell them to be careful, we’re warning them to look out because failure could be near.

Shouting “Be careful!” every time our confident kids encounter risk teaches them they aren’t capable of calculating and taking on risk themselves—it does nothing to guide them in the process. Child psychologists have long known that children learn best through their own experiences with their environment, but if we don’t allow or enable these experiences to happen, our children can’t learn from them.

Give kids more risk, not less.

In Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development, he proposed that children learn through their interactions with the world and develop new skills primarily through cooperative learning and scaffolding. This means that if we want our kids to learn how to manage and assess risk, the first step is exposing them to it. The next is guiding them through it.

Research agrees that children need real exposure to risk in order to learn how to manage it. In the review journal, Community Practitioner, researchers note that parental protection alone does nothing to limit a child’s long term vulnerability to risk. Instead, the research overwhelming proposes that parents and caregivers should help children “to experience risk, learn about danger, and develop strategies to manage situations in which risk exists.”

So this brings me to my final l reason I believe this phrase falls short—it’s so nonspecific. It conveys no truly useful information about how to better take care of oneself in the moment or in the future. In short, is it helpful? No.

When I yelled to my son to be careful, what I meant was, do you have one foot and one hand on the tree? Do you see the branch without pine needles? Do you know that means it’s dead and can’t hold your weight? There are so many things I could have told him that would have been more helpful.

Let’s change our language.

Steve Smith, chair of the Wilderness Risk Management Conference and a former mountaineering instructor for Outward Bound, writes there are three layers to assessing age-appropriate risk: recognition, evaluation, and management.

When we’re telling our confident kids to be careful, we are almost always concerned about one or more of these layers. But in nearly all cases, the point could be better communicated by supporting our kids through the risk assessment process—or as Vygotsky would say, scaffolding the experience for them so that in the future, it becomes something they can do on their own.

So skip the nonspecific, and give your child the information he or she may need to more accurately recognize, evaluate, or manage the risk ahead.

Instead of, “Be careful,” help them recognize the risk with something like, “Is there something for you to hold on to?”

Rather than, “Be careful,” help them evaluate the risk with something like, “Does that branch look strong?” or “Does that feel safe?”

And instead of, “Be careful,” help them manage the risk by trying something like, “What’s your exit strategy?”

Using phrases that empower our confident kids to manage risk on their own not only gives them important information about their environment, but it also teaches them that they’re capable of doing it. When we stop telling our kids to be careful and instead provide them with the useful and necessary information they need to make their own risk assessment, we build their confidence, increase their resilience, and give them the tools they need for independence.

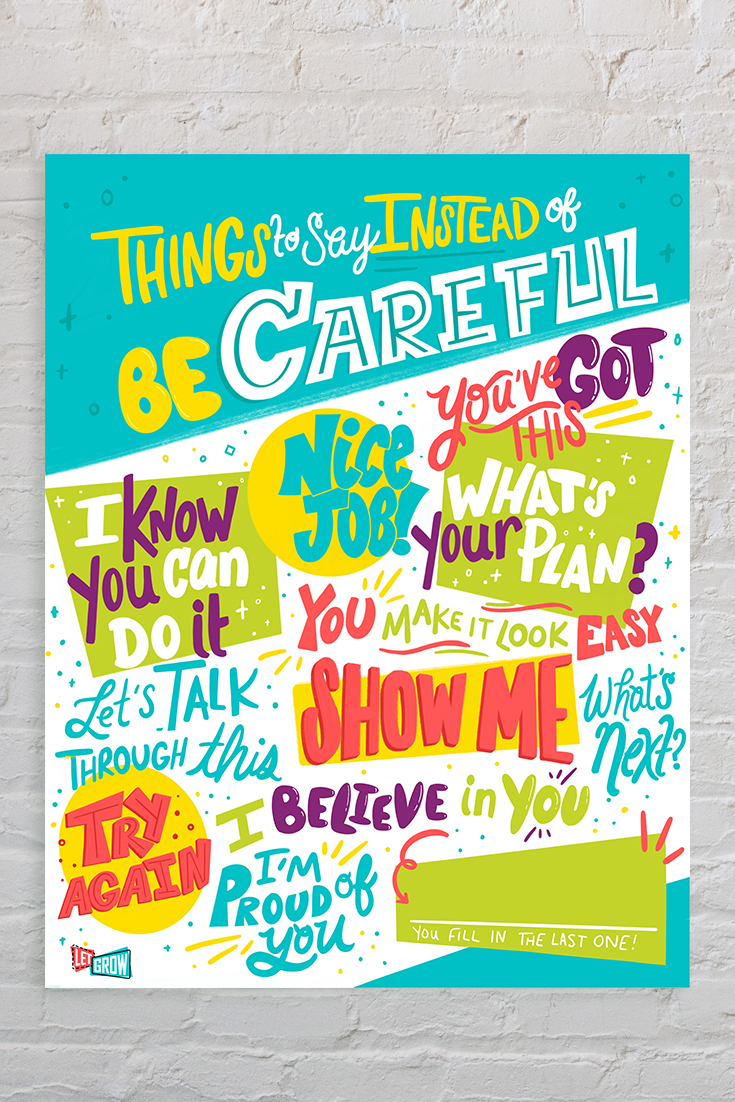

We created a poster about alternatives to “Be careful.” Check it out here.

Add your comment now using your favorite social account or login to your LetGrow account.